| . | . | |||

| . | Parallel LCR Circuits |

. | ||

| . | Aim:

1. To study the variation in current and voltage in a parallel LCR circuit. 2. To find the resonant frequency of the designed parallel LCR circuit.

Apparatus:AC power source, Rheostat, Capacitor, Inductor, Reisistor, Voltmeter, Ammeter, connection wire etc.

Theory:

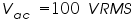

The schematic diagram below shows three components connected in parallel and to an ac voltage source: an ideal inductor, and an ideal capacitor, and an ideal resistor. In keeping with our previous examples using inductors and capacitors together in a circuit, we will use the following values for our components:

If we measure the current from the voltage source, we find that it supplies a total of 10.06 A to the combined load.

The Vectors:

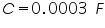

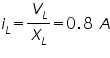

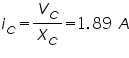

As usual, the vectors, shown to the right, tell the story. Since this is a parallel circuit, the voltage, V ,is the same across all components. It is

The Mathematics:

Now we have a pretty clear idea of how the currents through the different components in this circuit relate to each other, and to the total current supplied by the source. Of course, we could draw these vectors precisely to scale and then measure the results to determine the magnitude and phase angle of the source current. However, such measurements are limited in precision. We can do far better by calculating everything and then using experimental measurements to verify that our calculations fit the real-world circuit.

Where,

Now simply insert the values we determined earlier and solve these expressions:

These figures match the initial measured value for current from the source and fit the rough vector diagram as well. Therefore, we can be confident that our calculations and diagram are accurate. When When a circuit of this type operates at resonance, so that XL = XC, it must also follow that iL = iC. Therefore, iC - iL = 0, and the only current supplied by the source is iR.

Applications:

It can be used as

At resonance the effective impedance of the circuit is nothing more than R, and the current drawn from the source is in phase with the voltage. The resonance frequency in our example is 6.5 Hz.

Cite this Simulator: |

..... | ||

| ..... | ..... | |||

|

Copyright @ 2024 Under the NME ICT initiative of MHRD |

|

2.

2.  3.

3.  4.

4. 5.

5.

;

;  ;

;

the current that has different phases and amplitudes within the different components.

the current that has different phases and amplitudes within the different components.